There are numerous NPS limitations and pitfalls that will be examined in this post.

When we speak with companies about what non-financial metrics they use to assess performance, NPS ranks highly amongst three metrics. The others being employee engagement and customer satisfaction (CSAT). These same metrics appear regularly in Annual Reports to Shareholders. NPS and the other metrics are used to assess Key Management Personnel (KMP), who are subject to short-term and long-term incentives (STIs/LTIs) as part of their remuneration plans.

While NPS may be well known in Boardrooms and the C-Suite, it’s not clear if it is as well understood or liked. Its adoption appears to arise, not from its accuracy, predictive ability, actionability or validity, but from its simplicity, low cost of data collection, intuitive appeal, and effective marketing by large consultancies.

Indeed, NPS fails to satisfy many of the key characteristics necessary for corporate metrics to be useful, but that’s a topic for another post.

NPS – a short history

NPS was developed by Fred Reichheld, Bain & Company and Satmetrix around 2003. When launched, it was positioned as one simple question that can determine your company’s future and as the proverbial magic pill that will give participating companies a leg up on their competition. In short, it’s a metric promoted in a manner that has led companies to believe they need only measure a single metric. All they need is an advocacy score to predict future success and prosperity. We can’t think of any circumstance where a company would only focus on net profit to predict its future performance.

This has proven to be an almost irresistable and seductively simple proposition for many companies. If a company operates in an industry where there are only a few large competitors (e.g. banking, airlines, telcos, health insurance, etc) and the competitors are using NPS, what Board could possibly resist the urging of its institutional shareholders to also adopt NPS?

Invariably, though, when asked privately how happy NPS users are with using it, the feedback suggests a considerable amount of disquiet. It simply doesn’t deliver on its much-hyped promise of being the ‘silver bullet’ that fixes their business problems. Apart from anything else, this single metric simply doesn’t deliver the insights and actionability many desire.

NPS calculation

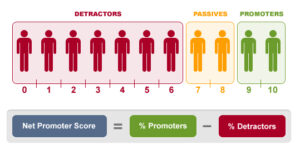

NPS is based on a single question; “How likely are you to recommend (us/a product) to a friend or colleague?” Survey participants respond on an 11-point scale (0 = not likely to recommend and 10 = extremely likely to recommend). Respondents are then categorised – a respondent scoring 9 and 10 is considered a ‘promoter’, 7 to 8 a ‘passive’ and 0 to 6 a ‘detractor’.

According to the guidelines, detractors are assumed to be customers or other stakeholders who are likely to say bad things about your company/product or service and even discourage others from using it. Promoters, on the other hand, are assumed to be the ones considered the most likely to spread positive word of mouth (as advocates).

The ‘Net’ in Net Promoter Score is derived by subtracting the percentage of detractors from the percentage of promoters. A resulting negative NPS means you have more detractors than promoters and a positive NPS means there are more promoters (that is, more potential positive word of mouth than negative word of mouth). This is a ‘one size fits all’ approach irrespective of the market setting or stakeholder group being assessed.

NPS limitation and pitfalls – what does Fred Reichheld think now?

In a 2021 article, Fred Reichheld (and others) publicly stated reservations about the use of NPS as follows:

“Unfortunately, self-reported scores and misinterpretations of the NPS framework have sown confusion and diminished its credibility. Inexperienced practitioners abused it by doing things like linking Net Promoter Scores to bonuses for frontline employees, which made them care more about their scores than about learning to better serve customers. Many firms amplify the problem by publicly reporting their scores to investors with no explanation of the process used to generate them and no safeguards to prevent pleading (“I’ll lose my job if you don’t rate me a 10”), bribery (“We’ll give you free oil changes for a 10”), and manipulation (“We never send surveys to customers whose claim was denied”). No details are provided about which customers (and how many) were surveyed, their response rates, or whether the survey was triggered by a specific transaction. Reports rarely mention whether the research was performed by a reliable third-party expert using double-blind methodology. In other words, some firms have turned Net Promoter Scores into vanity statistics that damage the credibility of NPS.”

NPS limitations and pitfalls – academic pushback

Not only has one of the principal architects of NPS had serious misgivings about how the metric is being used. There has also been significant debate in academic research circles.

Accuracy and predictive ability

Studies have shown that NPS may not be the most accurate measure of customer satisfaction. It has been criticised for not accurately differentiating between promoters and detractors and failing to predict loyalty behaviour effectively. The method of converting an 11-point scale into a binary scale of detractors and promoters can lead to a loss of information, particularly concerning “passive” customers (see later).

-

-

- Statistical validation of critical aspects of the Net Promoter Score, Cazzaro & Chiodini, The TQM Journal, April 2023.

-

Reliability and statistical support

Notably, a study by Kristensen and Eskildsen (2014) questioned the reliability of NPS as an effective indicator of customer retention. They highlighted that there is no evidence linking the growth or decrease of NPS with equivalent changes in business volume. The single-question approach of NPS does not consider psychological variables influencing purchase behaviours, and it fails to consider the intention of customers to repurchase a product or service.

-

-

- Is the NPS a trustworthy performance measure?, Kristensen & Eskilden, The TQM Journal, March 2014.

-

Methodological concerns

Baehre et al. (2022) revisited the use of NPS as a predictor of short-term sales growth and concluded that the methodological concerns raised by academics are valid. This suggests that using NPS as a standalone measure might not provide an accurate representation of customer satisfaction or loyalty.

-

-

-

The use of Net Promoter Score (NPS) to predict sales growth: insights from an empirical investigation, Baehre, O’Dwyer, O’Malley & Lee, Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, Volume 50, 2022.

-

-

It’s clear from these observations there are serious credibility issues and growing evidence of numerous NPS limitations and pitfalls. While Boards and management strive for simplicity, we all know that business is increasingly complex, no matter how attractive and appealing a single metric may appear.

In addition to the criticisms documented above, we describe below several further NPS limitations and pitfalls. This is done in the hope that Boards and the C-Suite carefully consider the use of NPS in their companies.

NPS limitations and pitfalls

NPS is a lagging indicator

NPS is based on past events/experiences, so it’s a lagging indicator. A high NPS doesn’t guarantee future behaviour. A customer who indicates a high likelihood of recommending a business may not necessarily do so. The correlation between stated intent and actual behaviour is weak to non-existent.

Lacks specificity

NPS scores are derived from a single general question about the likelihood of recommending a company/service or product. This approach does not capture specific feedback or reasons behind a customer’s score, making it challenging to identify areas for improvement.

Overemphasises promoters

NPS focuses heavily on promoters (scores 9-10), potentially overlooking the nuances of passives (scores 7-8) and detractors (scores 0-6). This can lead to a skewed understanding of the customer base and missed opportunities to convert passives into promoters. Loyal customers don’t always act as advocates for brands, services and companies. So how does NPS work if advocacy/loyalty isn’t the key driver?

Can be easily manipulated

As noted above by Fred Reichheld, companies can manipulate NPS via pleading, bribing and manipulating customer responses or by framing the question in a biased manner. They can manipulate the timing of a survey and target specific customers who are known to be strong supporters. These actions undermine the reliability of the score and, ultimately, company performance for the sake of short-term benefit.

Too simplistic

Customer relationships are multifaceted and can’t be accurately captured by a single score. NPS does not consider the depth and complexity of customer interactions and experiences, nor what underpins strong relationships.

Insensitive to change over time

NPS is a static measure and does not effectively track changes in customer sentiment over time. It does not capture the dynamics of customer loyalty in response to recent changes in products or services.

Neglects non-respondents

NPS surveys typically have low response rates, and the opinions of non-respondents are not captured. This omission can lead to an incomplete picture of overall customer sentiment.

Doesn’t distinguish between gaining detractors and losing promoters

Within the same industry or product vertical, NPS is problematic because there are many possible ways to arrive at the same number. For detractors, passive, and promoters respectively, we can arrive at an NPS of 20 in dozens of ways. A company with a 20 NPS could have 20% promoters, 80% passives, and 0% detractors, while another company with a 20 NPS could have 60%, 0%, and 40% respectively.

One could easily argue that the business that had 20% promoters and 0% detractors is very different than the one with a polarised customer base with 60% promoters versus 40% detractors, even though their NPS result is, for all intents and purposes, exactly the same.

Totally ignores passives

‘Passives’ (those scoring 7 or 8) are totally ignored when calculating NPS. It’s as if those stakeholders don’t even exist and their opinions don’t matter when the company is making important business decisions. If a respondent is likely to fall into this category, why would they want to respond in the first place, knowing their opinion will be ignored?

Not actionable and no new insight

Perhaps the strongest criticism we regularly hear from NPS users is that they invariably feel frustrated in not being able to take confident actions on the back of their results. This is because there are no obvious insights to be gained from a single number.

More to the point though, NPS is not actionable. What if you had a good one? What does that mean? For example, in the telecommunications industry, an 11% result for one company may be the best of the bunch. Is it the best because of the technology, the service, the wireless service, or the NBN speed and plan? The company is identified but what product or service is actually worth recommending, if any at all? We simply don’t know the answer to ‘so what?’

What if you had a bad NPS? What do you do? Is it a particular underperforming or unprofitable product or service that should be cut from the product mix? Is there a weakness in customer service or operational inefficiency that can be improved? This can be very frustrating for executives when performance bonuses are based on achieving a minimum NPS score. It is a temperature reading.

Only by understanding what actually drives customer loyalty can managers effectively prioritise their improvement efforts. Therefore, NPS can be classified as a ‘it is what it is’ metric. It reveals the obvious, isn’t predictive in any way, and doesn’t answer the ‘so what?’ question.

Doesn’t measure trust

Some companies talk about trusted relationships with their stakeholders and then quote a positive NPS as evidence. But NPS is not a measure of or a surrogate for trust. It’s a measure of potential advocacy.

NPS is one dimensional and it has a short-term focus whereas trust is multi-dimensional (driven by company trustworthiness) and is aligned to a long-term focus on achieving strategic outcomes and sustainability. Trust is a leading indicator and strongly influences financial performance and reputation.

An interesting observation is that almost all major financial institutions, whose behaviours were forensically examined by the Financial Services Royal Commission, used NPS as a KPI to assess eligibility for the award of executive bonuses. The low level of trustworthiness of those organisations was self-evident based on the Commission’s findings, despite whatever their NPS scores indicated to the contrary.

Based on bad calculation

NPS is based on a seemingly arbitrary 11-point scale (0 to 10). Why not a symmetrical scale like 0 to 4, 5, and 6 to 10? Or something else entirely? NPS is unipolar in the way the question is phrased ‘How likely are you to recommend?’, while bipolar in how it’s applied – detractors versus promoters. A 0 to 6 response means ‘not likely at all to recommend,’ which is very different than someone actually detracting or stating negative attributes and why. The application of NPS is inconsistent with the scale used.

Furthermore, by converting an 11-point scale into a 2-point scale of detractors and promoters (removing the passives altogether), valuable information is lost. The binary scale doubles the margin of error around the net score (promoters minus detractors) and that means that if you want to show an improvement in NPS over time, it takes a sample size that is around twice as big to calculate the difference, otherwise the difference won’t be distinguishable from sampling error.

In summary

There are compelling reasons to question the efficacy and utility of the NPS metric. There are numerous NPS limitations and pitfalls.

It’s never a good idea to put all your measurement eggs in one basket. Consider multiple measures, including those that directly assess trustworthiness and stakeholder trust which are essential to the success of any company. They should certainly rank higher than any measure of advocacy, like NPS.

Risk is a function of the quality of information at your disposal to make the best decisions. So, if you are currently reliant on NPS (or thinking about it) as a standalone metric, we recommend you look for additional metrics that can provide greater surety and confidence to underpin your decision-making and earn the trust of your stakeholders.

Regardless of whether or not you’re using NPS, we encourage you to be clear about the decisions you’re making and gather the best evidence you can in service of making those decisions, not just the evidence that’s most convenient.

What do you think?

When performed with the right intent and a high degree of execution, your company’s actions can earn trust with its stakeholder groups. Trust is a strong differentiator and a dominant driver of future business profit and growth.

We’ve made trust tangible with our Trustgenie service – helping companies measure, manage, and improve their trust performance to increase revenue, reduce costs, mitigate risks and protect reputations.

If your company is ready to make trust its superpower, Trustgenie can help.